Immigrant labourers Vs local residents : Shantipura pays for Progress

By Philip Mudartha

Bellevision Media Network

Udupi, 11 Apr 2013: Let me tell you this true story of my native village in coastal Karnataka. Population is approximately 4,000 living on farmlands of about eight square miles. Roughly 40% are Catholics, who are good agriculturists and floriculturists. They train their men-folk into mechanics, stewards, priests and drivers and export them wherever they are needed. They also export their women-folk all over the world as nuns, nannies, nurses and secretaries. Those, admittedly, “not of export quality” remain behind and tend to run the village affairs.

I have annually updated my “census” of the village. It has a Catholic Church and a Protestant Prayer Hall to serve the Christians. The Hindus have four Temples (devastanas), half a dozen shrines (mandirs), and a dozen oracles (banns). All of them lived peacefully in harmony, so we changed its name from Pamboor to Shantipur.

I have annually updated my “census” of the village. It has a Catholic Church and a Protestant Prayer Hall to serve the Christians. The Hindus have four Temples (devastanas), half a dozen shrines (mandirs), and a dozen oracles (banns). All of them lived peacefully in harmony, so we changed its name from Pamboor to Shantipur.

All was well till someone had a brilliant idea and he started to drill holes in appropriate places and discovered high quality construction materials, granite included, under the earth. These not so brilliant started to mine the abundant black rocks for stones.

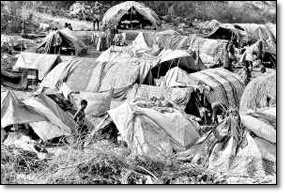

As none of the natives had skills in drilling and use of explosives, hordes of “immigrant skills” were brought in “sponsored” by those who managed to weasel out quarry permits from Geological Authorities. These poorly paid, and sometimes unpaid, miners lived in squalid huts by the roadside on public land and “polluted” the village. Or so the natives thought when the bare breasted immigrant men, women and children urinated, defecated, and bathed in the open. Wealth came from the front door; noise, dust and disease from the rear. Peace was shattered.

As none of the natives had skills in drilling and use of explosives, hordes of “immigrant skills” were brought in “sponsored” by those who managed to weasel out quarry permits from Geological Authorities. These poorly paid, and sometimes unpaid, miners lived in squalid huts by the roadside on public land and “polluted” the village. Or so the natives thought when the bare breasted immigrant men, women and children urinated, defecated, and bathed in the open. Wealth came from the front door; noise, dust and disease from the rear. Peace was shattered.

“Diana is in hospital at Manipal, down with strange fever,” said Mike, my class-mate and neighbor, now a local banker. “It is them or us”, he warned in a conspiratorial tone as he hurried off to see his teen daughter. Such was his desperation, anger and intolerance that he totally ignored to enquire after me and my family, a customary ritual when emigrant natives return on vacations.

I climbed the tallest hillock in the village and looked around to take in the green beauty of the land with its paddy fields, coconut groves, and flower gardens. I stayed till after it was dark and saw houses of the affluent lit with bright lights. I made my way home through the lane lined with unlit straw huts, smelling of urine and cheap country liquor, where men and women quarreled and yelled at each other and children cried at full –throat.

I climbed the tallest hillock in the village and looked around to take in the green beauty of the land with its paddy fields, coconut groves, and flower gardens. I stayed till after it was dark and saw houses of the affluent lit with bright lights. I made my way home through the lane lined with unlit straw huts, smelling of urine and cheap country liquor, where men and women quarreled and yelled at each other and children cried at full –throat.

When I returned to my home here in Qatar, I sent my musings to the village bulletin and asked my villagers to ponder: “Who is to blame for the apparent rise in disease and disharmony in the village? The immigrant who break their backs with the rocks? The local businessmen who own and run the quarries? Or the village council (run by village representatives and where the quarry workers are not represented) that has willfully filed to preserve the environment while exploiting the natural resources? Or who?”

Intolerance comes easy anywhere in the world. But development needs hands. And hands come with dogs, skirts, and often bare chests. Five fingers of a hand are not alike.

The 540- words note I reproduce above was published by Gulf Times, Qatar on 7th September 2002. Ten years before I wrote those lines, I was in Brazil and I bought T-shirts with Rio Green Earth- 1992 logos and catch phrases. A fortnight after I wrote those lines, I was in Lapland in Northern Sweden and I had piping hot tea inside an Ice-hotel in the company of miners of different kind. The two experiences were entirely at variance to each other; diametrically opposed. Is progress possible without damage to local social fabric, ethos and ecology?

The 540- words note I reproduce above was published by Gulf Times, Qatar on 7th September 2002. Ten years before I wrote those lines, I was in Brazil and I bought T-shirts with Rio Green Earth- 1992 logos and catch phrases. A fortnight after I wrote those lines, I was in Lapland in Northern Sweden and I had piping hot tea inside an Ice-hotel in the company of miners of different kind. The two experiences were entirely at variance to each other; diametrically opposed. Is progress possible without damage to local social fabric, ethos and ecology?

Almost eleven years after I wrote those lines, I am poised to leave Qatar and return to my homeland. Has my homeland found the right answer that I thought the Swedish have found but the Brazilians had not?

What is your take? Tell me and let me construct a sequel to this story with your help.

|

Philip Mudartha

|

| Comments on this Article | |

| Philip Mudartha, Pamboor | Wed, April-17-2013, 11:59 |

| These are exciting, well articulated and very revealing views. All of them come from immigrants, who mostly hold pro-immigrant liberal views. What views the local businessmen hold? Do residents, main beneficiaries of inward remittances of their emigrant relatives and by services of immigrant labor endorse these views? What campaign position was held by the ward members in the GP, TP and ZP on this subject? Did a quarry contractor elected to represent them? Any volunteer to provide answers? | |

| Ronald Sabi, Moodubelle | Mon, April-15-2013, 12:07 |

| Comments are as good as article. All of them are thought provoking. Poverty is not permanent. Discipline of one generation head will bring prosperity to immediate one. Sometimes, one person of a family leading dedicated life with or without future vision may be able to turn around the cycle. Children of rich and educated too may reach street due to bad company, drugs and lack of parental guidance. | |

| Michael Sequeira, Shantipur/Nairobi | Sun, April-14-2013, 2:21 |

| I agree with Peter Saldanha.The local council should come up with strict policies to ensure the villagers,the immigrant work force and the owners of the quarries who hire these immigrant workers folllow the discipline required to keep a clean environment.Keeping the environment clean requires a lot of discipline,determination and understanding.It is possible with proper education and instilling the discipline necessary to bring the change.It is the responsibility of the local council and they have the mandate to carry out.I am sure they have the resources,revenue and power to provide the best environment. | |

| Peter Saldanha, Bangalore | Sat, April-13-2013, 1:26 |

| In my opinion, it is the responsibility of the village council (gram panchayat) to preserve the environment. Having said that it is the collective failure of our system and villagers as responsible council members. Any Indian Citizen has the right to travel and live in any part of India but he or she needs to adhere to the local administrative guidelines. The council should ensure that the migrants have been paid minimum prevailing wages to live their daily lives ofcourse with dignity and respect. Now the local businessmen come under the purview of the village council and the council has every right to tax them and increase its source of income as they are exploiting our village resources and creating wealth. We as responsible members of the council have every right to question the elected representatives on health and sanitation issues arising out of these migrants. It is one of the responsibilities of the panchayat to look after villagers health and hygiene by providing basic facilities. | |

| Norbert, Mangalore | Thu, April-11-2013, 11:48 |

| A very realistic and thoughtful comment by Victor Castelino. I could not help my myself but to agree with him completely. This is reality, this is change and this is how civilisations have transformed, societies have developed. There is nothing to brood here. But for these less fortunate in-migrants our roads would not have been laid or tarred, houses would not have been constructed, schools would not have been built. In short the change that we have witness in our neighbourhood is made possible by the labour of these inmigrants. Same thing is true in Gulf countries – but for our brethren ( Coastal Karnataka and Kerala) the life in Gulf would not have been what is it is today. Let us move with time and enjoy the change being in harmony with the environment rather discriminating between we v/s they , locals v/s in-migrants. | |

| Victor Castelino, Dubai | Wed, April-10-2013, 10:47 |

| We have come to a full circle. A century or so ago our place was just like the one you have described! Only the local labourers are replaced by the migrant labourers! I studied in a primary school where there were no toilets and almost a thousand students urinated around the school daily and no one complained. It was part of our life. Our church had no toilets either. While men stood against a tree and pulled out their "little thing" and relieved themselves, women hid themselves behind a bush and relieved themselves. No one said anything. When I moved to the high school, it was the same story. It was natural for every one to urinate where ever one felt comfortable. At home, being a member of the farming family, urine was collected and used to manure vegetable plants, jasmine plants etc until it was replaced by urea and cow manure replaced by "suphala" etc. Until then no one spoke about environmental damage because urine and excreta of animals were considered natural animal waste. Now we use chemicals as manure and people think that it is normal. Now we use pesticides to control pests whereas in our days we used dry ash and palms of certain trees as pest control agents. Our women toiled in rice fields bare breasted, the koraga women roamed around bare breasted and no one bothered. We all bathed in rivers and rivulets, jumped in to wells and lakes wearing a small piece of cloth and no one noticed because it was the way every one lived then. Then all of a sudden every thing changed. A high school was built for us to further our studies and bridges were built to cross the rivers. Every half an hour a transport was available to move from one place to another. So when we completed high school we could attend colleges and get degrees. Our fore fathers stopped paying "geni" thanks to land reforms. There were scholarships and free education available from the government. Money was not a problem. With degrees in hand, money a plenty to pay the agents, our young generation moved to Gulf countries and helped their siblings to pursue the highest studies possible. Now who wants to stay in a village and waste one s talents? Moved to US, Canada, Australia, UK... The world was vast and the opportunities were beckoning. Those who preferred to stay back had enough money to build bungalows with attached toilets to every bedroom; enough money to buy food grains and vegetables. So urine became redundant and environmental hazard. Cows became hazardous because they produce gas and pollute the atmosphere. The only problem was the vacuum created by our migrant workers which was filled by less fortunate outside migrant workers. They do exactly what we used to do. There were drunkards fighting then, so too now. There were open air toilets then, so too now. It will continue until the present migrant workers children get degrees and migrate and improve their lot and that of their parents and siblings only to be replaced by another lot of less fortunate migrant workers. They may be a nuisance for the affluent residents, but they are helping to develop the country s infra structure which will be used by the same people who complain against them. This vicious circle will continue for many many years to come. Meantime, the local administration should help them to live a decent life. They are Indians and they have every right to move wherever they like. Whether we like it or not, they are a part of our society and we have to live with them. | |

Write Comment

Write Comment E-Mail To a Friend

E-Mail To a Friend Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter  Print

Print  [..FIRST rank holder of St. Lawrence High School. He not only inscribed his name on the hearts and minds of every Bellean and the neighboring villages, but through out the State of Karnataka as TOPPER of SSLC Board Examinations in the year 1969..]

[..FIRST rank holder of St. Lawrence High School. He not only inscribed his name on the hearts and minds of every Bellean and the neighboring villages, but through out the State of Karnataka as TOPPER of SSLC Board Examinations in the year 1969..]