Wasting our youthful demographics

By Philip Mudartha

Bellevision Media Network

25 Apr 2024: India has recently become the world’s most populous country. 68% of its population is working-age individuals between the ages of 15 and 64.

This demographic structure, referred to as a demographic dividend, has the potential to generate very high economic growth if India can create productive employment opportunities for its large working-age population.

Youth boom, yes. Job boom, no:

At the markets in Navi Mumbai where I shop for groceries, vegetables and fruits, young women and girl-children accost me and implore to buy garbage bags for a few tens of rupees. I wonder if they earn enough for two square meals a day. Then there are Swiggy, Zomato and other platforms whose delivery boys arrive at our door-steps with freshly cooked food from restaurants, daily essentials like fresh milk, eggs and bread etc. Have you wondered what they must be earning per day? Their ride is by self-owned two-wheelers; they pay for the petrol and other vehicle expenses. They must own a smart-phone and purchase the mobile data. After all these costs, how much do they save in a month? Ten thousand rupees; or, may be twelve? God forbid, if they deliver the parcel at a wrong address; the refund that the aggregator makes to the affected customer is deducted from the delivery boy’s salary. The pertinent question is why there are so many Indians like them, and so few like those who afford their services? We see many young Indians working difficult, low-paying jobs in delivery, logistics and construction.

The rhetoric about “Viksit Bharat”:

The Lok Sabha election campaign is at full throttle. PM Narendra Modi is pitching for another term. Viksit Bharat is his guarantee. He insists that he is the best choice for a young and aspirational country. Some of the successes the government claims are indeed very real. Since 2014, India has seen 54,000 kilometres of new national highways built. The number of Indians taking flights has doubled to 200 million. The government has invested in both physical and digital infrastructure, with flyovers, metro lines, electrification, direct cash transfers, UPI, and telecom connectivity. It’s a big deal for a country that had become used to potholes and power cuts.

But our progress has a glaringly big flaw. In the recent Lokniti-CDS survey of 10,000 voters, unemployment was the top worry for 27%. 62% said that finding a job had become even harder in the past five years. India’s unemployment rate, which is around 8% according to the private institution CMIE, is higher than other Asian economies at a comparable development stage.

Some 45% of the workforce continues to toil on farms in the agricultural sector, while in the non-agricultural sector, 74% of workers are employed in low-paying informal work in microenterprises.

Among young people aged between 15 and 29 years, approximately 28% are engaged as “unpaid helpers in household enterprises.” And here too, the agriculture sector remains the principal source of employment, accounting for 36% of employed youth.

Ours is a young country, the ’world’s next workforce’. But our youth boom is challenging our policy makers: how are we going to provide these hundreds of millions of young people with jobs, and add to our productivity and growth?

India will need a radical reorientation of its growth strategy if it is to address the challenge of productive job creation and harness its demographic dividend, making the growth process more employment-intensive. India needs to ramp up on job creation, fast.

A youthful country, looking for work

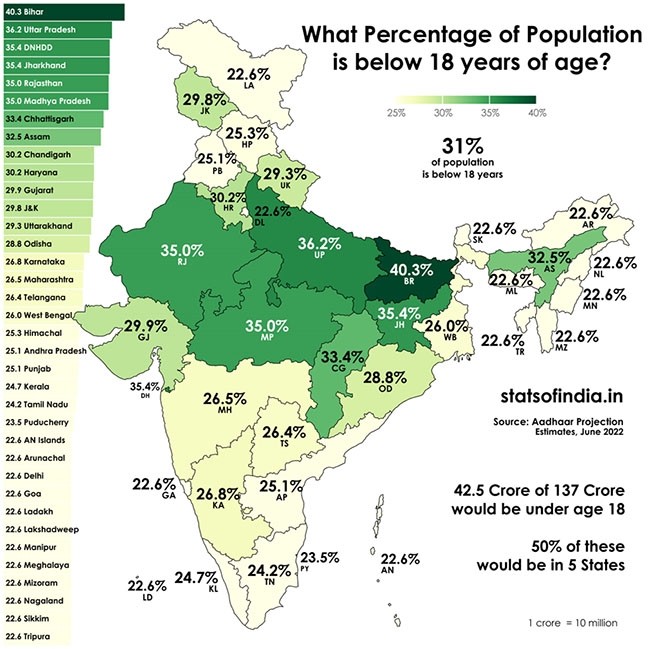

The median age of Indians is 29 years, compared to 39 in the US and 40 in China. Nearly half of our population is under the age of 25. India’s youth is not evenly spread out - they are now concentrated in the north.

Over the last three decades, a big shift has happened in the Indian economy. The south and west of the country, which have long been the main drivers of growth, have grown older. Population shifts put more young people in poorer states.

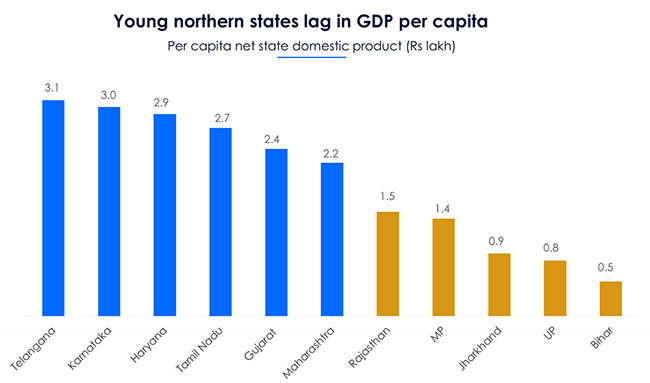

The south and west of India still dominate in GDP contribution to the economy, and in GDP per capita. The Hindi heartland states, which have the youngest populations (Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and UP, BIMARU) have a low industrial base, making this a low GDP-per-capita region.

There are not enough schools in the northern states. The classrooms are crammed with high student to teacher ratio, resulting in low education levels. These students come from farming families. After finishing school, they seek jobs in non-agricultural sectors. However, lack of job skills make them unemployable.

The youth in Southern states are better educated and therefore find employment in high-end services, like IT and finance. For the low-skilled youth from BIMARU states, productive employment can only be in labour intensive manufacturing. The Chinese experience has shown that the central focus of a national growth strategy should be job creation for the masses.

Between 1978 and 2010, the share of employment in Chinese agriculture declined from 70.5% to 36.7%. In India, the corresponding shares declined at a slower pace from 71.1% to 51.3% during the same period. The Chinese absorbed the surplus workforce in labour intensive manufacturing for exports.

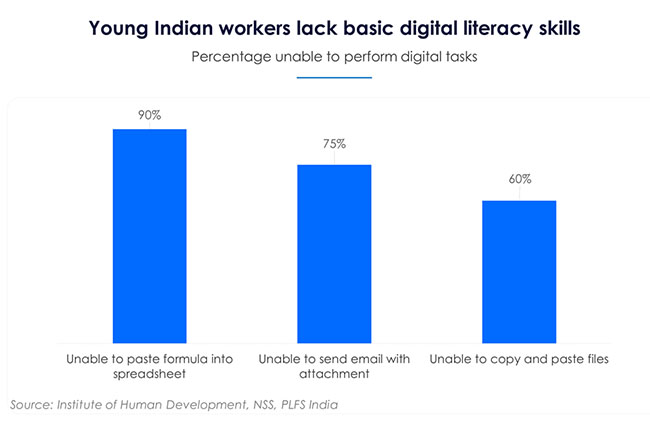

The youth unemployment rate for Indians who cannot read or write is 3.4%. But the unemployment rate is 6 times more for those who have completed secondary education (18.4%), and 9 times more for college graduates (29.1%). A digital skills survey showed large percentages of Indians are unable to complete basic digital tasks.

The path forward

At present, 83% of India’s unemployed are young people, and 90% of workers are in informal work. India’s government sector employs only 5% of the population, so private job creation is key.

India must embrace a two-pronged approach to achieve labour-using industrialization: 1) incentivise the entry of formal firms into labour-intensive sectors and 2) raise the competitiveness and productivity of the many small and medium enterprises that dominate labour-intensive industries.

Many international firms have begun to look to the Indian market in order to diversify their businesses and investments beyond China.

The success of Bangladesh in export-oriented labour-intensive ready-to-wear garment is an example.

But the problem is not just in the supply of jobs, but also the quality of people looking for work. So most of all, India needs to take a U-turn in its school and health policies, and raise investments here. This is crucial to build the innovators and entrepreneurs who create jobs, and the high skilled workers who attract investment.

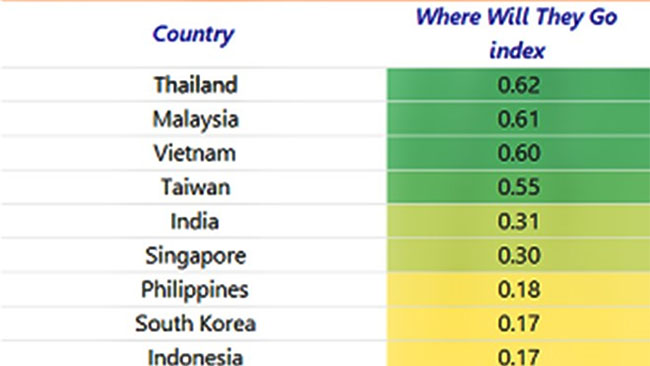

Foreign investment has lots of countries competing for it right now: India, Thailand, Malaysia, Vietnam, Taiwan, Indonesia etc. It will go where there is high-quality human capital. If we fail to prioritize education and health spending, we will do India’s youth a great disservice, condemning them to bad schools and indifferent jobs. The time to act is NOW!

Our handicap is that the literacy rate is still low at about 74% for the population aged above 15 years, compared with 97% and 95% for China and Indonesia respectively. Besides, technological developments are common which reshape labour markets by making some jobs obsolete but creating new ones. Retooling existing jobs that require new skill combinations must be a continual endeavour.

Against this backdrop, policymakers need to adapt education and skilling systems to ensure that Indiana can meet the complex and evolving skills demanded by an ever-changing world of work.

Women empowerment is fundamental

No nation can progress socially or economically if its women are left behind. If the women are not educated, if they are not safe, and if the gender discrimination exists then the nation cannot progress and prosper.

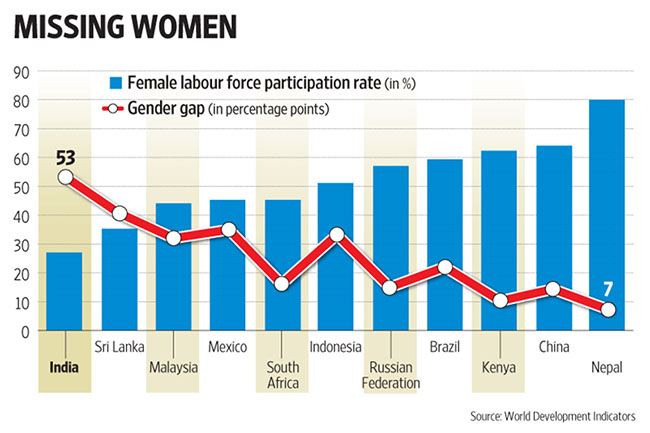

We will not realize our demographic dividend unless we bring more women into the labour force and productive employment. At present, India’s female labour force participation rate (FLFPR) stands at 37%, with 64% of all employed females in the agriculture sector. The FLFPR is abysmally low in urban India.

India is among the worst performer in bringing women into gainful employment. The national effort requires to address regressive social and cultural norms. It also requires investment in childcare service provision, health, education and technology, and infrastructure services.

Further, it is important to improve access to decent, productive and well-paying employment opportunities for women. India must adopt a macro policy framework that supports gender-equitable inclusive growth and more jobs for women.