We are poorer than Bangladesh!

By Philip Mudartha

Bellevision Media Network

01 Nov 2020: The recent International Monetary Fund (IMF) press release on Gross National Product (GDP) numbers of member countries shocked many Indians. Egos were hurt, especially of our government supporters, according to whom Modi is doing a good job of running the country and managing its national economy.

This is not really an Act of God:

India’s economy was spiraling down for over two years before the announcement of national lockdown in the wake of Covid-19 pandemic on 23rd March 2020. The corona pandemic was termed as an “Act of God” by the Finance Minister. She implied that the economic slowdown cannot be blamed on the policies of her government. None, except Modi acolytes, were convinced. Most experts agreed that the economy was mismanaged by the government. Especially, the daft demonetization in Nov 2016 followed by the chaotic implementation of Goods & Services Tax (GST) in early 2018 disrupted economic activities. The demonetization destroyed small and medium businesses in the informal sectors operating on cash basis. Livelihoods were lost in the informal sector, which employs bulk of unskilled workforce. By FY2017-18, the nation-wide unemployment rate clocked 6.1%, a record 45-year high. Then the GDP growth for FY2019-20 tumbled to 4.2% from 6.9% that Modi inherited in FY2013-14. This was the lowest since the economic reforms legislated in FY 1991-92.

The draconian lockdown and its brutal enforcement:

PM Modi, characteristically, announced the nation-wide lockdown on 22nd March 2020 without any notice. It was brutally enforced without required deliberation and planning. All economic activities ground to a halt. It was said that such a draconian lockdown would stop the spread of corona virus and save lives. Seven months later, the pandemic has spread not only in metropolises but also rural towns. The economic distress and the unemployment are there for everyone to see. At the time of writing on 29th October 2020, the total national corona virus tally stands at 80 lakhs, 40 thousand and 203. The government data puts the deaths at 1, 20,527 which is the second highest in the world after the US.

The Indian economy has contracted by a record 23.9% in the April-June 2020 quarter. The real GDP fell to 26.9 lakh crore in constant terms, 23.9% lower than a year ago, according to government data released by the Ministry of Statistics and Program Implementation. Nominal GDP fell to Rs 38.08 lakh crore, 22.6% lower than a year ago. In gross value added terms, the economy contracted by 22.8%.

We are poorer than Bangladesh!

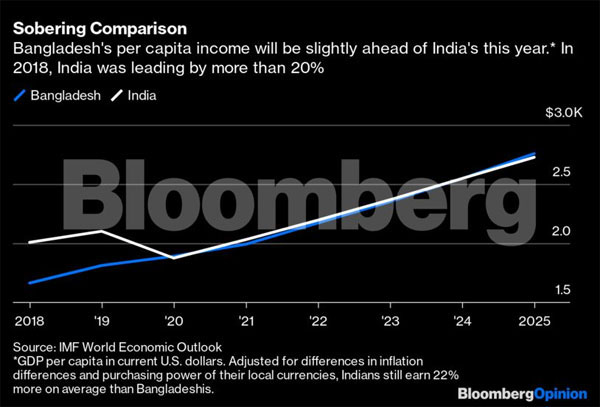

Our national Covid-19 economic gloom turned into despair when news that our per capita GDP would be lower than in neighboring Bangladesh, from this year. “It’s shocking that India, which had a lead of 25% five years ago, is now trailing,” tweeted Kaushik Basu, a former World Bank chief economist. Ever since it began opening up the economy in the 1990s, our national dream has been to emulate China’s rapid expansion. After three decades of persevering with that campaign, slipping behind Bangladesh hurts our global image. What’s worse, the severe economic lockdown India imposed to stop the spread of the disease is set to wipe out 10.3% of real output, according to the IMF. That’s nearly 2.5 times the estimated global loss.

GDP of India Vs Bangladesh

Where have things gone wrong?

The mis-management of corona virus pandemic is definitely to blame. Bangladesh’s new infections peaked in mid-June, while India’s daily case numbers are starting to taper only now, after hitting a record high for any country. With 165 million people, Bangladesh has recorded 5,861 Covid-19 deaths. While India has eight times the population, it has 20 times the fatalities. The death rate for Bangladesh is 35.5 per million, whereas for India it is 91.3 per million (India’s at 257% that of Bangladesh). Evidently, Bangladesh has managed the pandemic better than us.

Worse, as said earlier, even without the pandemic, India might have eventually lost the race to Bangladesh. Pennsylvania State University economist Shoumitro Chatterjee and Arvind Subramanian, our former chief economic adviser, have co-authored a research paper titled “India’s Export-Led Growth: Exemplar and Exception.” According to them, Bangladesh is doing well because it’s following the path of previous Asian tigers. Its slice of low-skilled goods exports is in line with its share of poor-country working-age population. Vietnam is punching slightly above its weight. But basically, both are taking a leaf out of China’s playbook. The People’s Republic of China held on to high GDP growth for decades by carving out for itself a far bigger dominance of low-skilled goods manufacturing than warranted by the size of its labor pool.

A personal anecdote will prove the above thesis:

I have been a frequent visitor to the US for four decades. In the late seventies of the previous century, I would walk into Macy’s, a retail store in downtown New York, and find a man’s shirt for a dollar a piece, tailored in South Korea, the foremost among the Asian Tigers. In the nineties, shirts made in China replaced the South Korean products. Since a decade or so, shirts made in Bangladesh, Vietnam and Laos have taken over the shelves. Besides, there are an assortment of cheap goods that the Americans buy like stationary items, pens, pencils, paper clips, needles and so forth which were formerly made in China but now made in Bangladesh. These are manufactured in small factories which employ cheap and low-skilled labor, especially women. The share of women in labor force is 36.4% compared to a mere 20% in India. The female workforce participation rate in Laos is 77% and in Vietnam 73%. Both countries are competing with Bangladesh to be the next China in our neighborhood.

India has gone the other way:

India has chosen not to produce the things that could have absorbed its working-age population of 1 billion into factory jobs. “India’s missing production in the key low-skill textiles and clothing sector amounts to $140 billion, which is about 5% of India’s GDP, according to the research paper mentioned above. The real loss is $60 billion in foregone exports from low-skill production. It’s real, and yet nobody wants to talk about it. Policymakers don’t want to acknowledge that the shoes and apparel factories that were never born, or were forced to close down, could also have earned dollars and created mass employment. They would have provided a pathway for permanent rural-to-urban migration of low educated masses.

“Are we poorer than Bangladesh? Never mind. We can erect barriers to imports and make stuff for the domestic economy. Let’s create jobs that way.” That seems to be what the ruling BJP and its politicians say instead of making amends for past mistakes. In fact, PM Modi has re-branded the 1960s and ’70s slogan of “self-reliance” as “atm-nirbhartha” as his signature economic slogan in the wake of the stand-off with China at the frontiers. There can be no greater mistake for a lower-middle income economy with an Export-Import trade deficit of several billion dollars.

Trade has worked for the country:

India has been an exemplar of export-led growth, doing better than all countries except China and Vietnam. However, the glass is half full. It’s the composition that’s wrong; because, as the research paper details, ours is an unusual “comparative advantage–defying specialization.” India exports a lot of high-skilled manufacturing goods and services, such as computer software. But as the world’s factory, China is now ceding room to others at the lower end of the spectrum. That is where India’s opportunity lies: We have the competitive advantage of our cheap and not particularly well-educated labor that needs factory jobs in small and medium sectors, manufacturing mass consumption goods for exports to markets like the US, Europe and beyond. Given the urgent challenge of creating at least 120 million new jobs immediately and then at least 8 million jobs year after year, it’s also the country’s biggest post-pandemic headache.

The unemployment rate tells half the story:

The migrant labor walking back to their home villages

The worker population ratio is a mere 46.8% in India. The youth unemployment rate is around 25%. Men and women employed in the organized sectors retire by the age of 60, and idled even when they are healthy considering the higher life expectancy of 72 years. For a nation with 1320 million people, with 6% above 65 years age and 30% below the age of 18 years, a 64% is available for gainful employment. This is a massive 845 million people of whom 228 million are not workforce participants. Even if 50% are inducted into the workforce, mainly women and those between 60 and 65 years and the underemployed agriculture laborers, there is a need to create employment opportunities for over 114 million people immediately. This can only be done by a central government working in tandem with state governments to create an ecosystem of export-oriented MSMEs in the private sector. Towards this end, there is an urgent need to reform our financial system, especially of micro-finance and assisting self-help groups at village levels. Towards this end, it is time to look not at China but at Bangladesh, Vietnam and Laos and emulate what they have done which we should do but hadn’t.

There is no social security for our labor:

Fig 2 above represents the migrant crisis. These ill-educated, unskilled, poor and cheap laborers found themselves without a job as soon as the national lockdown was announced. They had no option but to walk thousands of miles to their home villages in the Hindi heartland from big cities where they worked in unorganized sectors. None of them have a social security frame-work. They do not receive any government dole as unemployment benefit unlike in richer countries like US where the newly unemployed received handsome governments paychecks. Even in organized sectors including “good quality employers in the economy” are increasingly hiring temporary “contract workers” at a fraction of normal wages. They do not have any kind of “unemployment benefit” as soon as their job contracts are revoked. This speaks volumes for our “socialist” system of governance which we love to hate in our new-found love for right-wing market-oriented economic systems.

The labor and agriculture reforms enacted by Modi government:

The Modi government has been hyper-active in recent times in pushing its own brand of reforms in education, labor and agriculture. I have dealt separately earlier on the farm reforms and the national opposition by farmers and their associations out of fear of big corporate houses taking away their livelihoods. The labor laws reforms have not yet caused much debate, mainly because the trade unions have long lost their influence and the leftist political parties have very low political capital. While their intent cannot be faulted, the outcomes might not be as desired. Using the parliamentary process to bulldoze the opposition, wider debates did not take place before enacting these laws. The ill-effects will soon be felt especially as they have come at the wrong time when the pandemic has put nearly a quarter of the workforce out of their jobs. Instead of emulating China and now Bangladesh, we might be staring at single digit GDP growth in the coming years.

************.

Further Reading:

1. The Payment of Wages Act, 1936, the Minimum Wages Act, 1948, the Payment of Bonus Act, 1965, and the Equal Remuneration Act, 1976.

2. The amended labor codes with respect to the above.

3. The new Code on Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions Bill.