The other face of Summer Olympics 2016 Host City: Rio

By Philip Mudartha, Doha

Bellevision Media Network

Doha, 22 Aug 2012: As I wheeled my luggage through the exit door at Rio de Janeiro international airport, a pair of gun-toting toughies took charge of me and my belongings. They gently but firmly eased me into a waiting deluxe limo. As it screeched out and merged with the traffic on the expressway, I spotted two cars following me, keeping a respectable distance; one in the rear and other in the parallel lane.

Was I kidnapped? No such luck! My Brazilian hosts had made elaborate private security arrangements for my safety. That was a little under five years ago. Rio was then in tough competition with half a dozen aspirant cities-including Doha where I came from- to host 2016 Summer Olympics.

The toughies escorted me into my hotel, a luxurious sea-front property at Copacabana, where global celebrities and moneybags come to acquire their tan. When they left me, I had detailed instructions on what I should not do. One of them would be on call 24/7 at my service. I must call him if I wanted to step out of hotel and tour the city. Hmm; some fun life this, in the city that does not sleep!

My Rio adventures to run from the gilded cage:

I changed into my Copacabana two-piece wear and was on a city bus within half an hour, throwing caution to winds. My first stop was Corcovado, the hill hosting the protector of the city, “Christ the Redeemer”. The day ahead was sunny, bright and long. I had been to most of the tourist attractions. The cable car ride to Sugarloaf Mountain excited me as much as the train rides from Corcovado to Cosmo Velho. Standing at midfield Maracana Stadium, I felt like Pele. If paddling a boat in Rodrigo de Frietas Lagoon drenched me in splashed water, profuse sweating was reserved for jogging in Tijuca National Park. Between each stops, I refilled my energy levels with papaya juices and a mid-day meal of rice, beans and grilled fish on a pavement.

Through all this, I was discreetly watched upon from a respectable distance. I had spotted my bodyguards even as I had first gotten off my bus at Cosmo Velho. When the sun was about to set, I knew my freedom-in-Rio-at-large act must end. Public buses are no longer safe. It was time to call for my protectors-to get to know them.

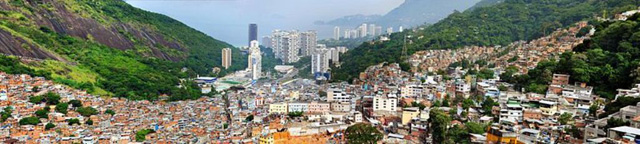

The favelas make their presence felt too:

Could we ride across the Guanabara Bay into Niteroi? I had come to Rio four times in twenty years, but it would be my first time in Niteroi, the satellite city connected by the 14km long marvel of an 8- lane President Silva Bridge. They were pleased. Ah, we are going home, they beamed. Would they like to show me around their homes? Ah, no, Senor. We are favelados, the slum-dwellers. I thought favelas are for mulatto, the Bahia, and the Blacks. Did I know about gentrified favelas? No. My white and brown Brazilian friends had always talked about favelas and the poor, angry, dangerous, mostly black people living in them. I did not know tall handsome brown men in business suits and neck-ties would come from favelas. My earlier bus rides were meant to meet and talk to favelados in the first place. If I had known I was guarded by them, I didn’t have to take the trouble!

According to official surveys, nearly 12 million Brazilians live in favelas, the slums. In Rio, there are more than 1000 of them. Some of the notoriously famous are within walking distances from famous beaches of Copacabana, Ipanema and Leblon. One in five Carioca, the Rio citizen, lives in favela colonies on the hills. Anyone who had emigrated from rural agrarian homes in search of a job on urban streets in any country knows how demeaning and dehumanizing life can be in a slum. I have known it firsthand in Mumbai ten years before my first trip to Rio. It is a daily struggle to get water, access the toilet and wade through excreta and garbage to the main street. And not encountering the drunkards, maniacs, goons and slumlords, of course.

My gentlemen Favelados did take me around in their safe car, with two pilot cars throwing a protective cordon. They even allowed me to drink from a bondo (tender coconut) from a favela hawker at half the price it sells at Copacabana. But, to my dismay, they did not let me into their neighborhood. Years later, I saw pictures of US President Barak Obama walking the streets of City of God Slum Housing waving at admiring favelados and flashing his trademark smile. Mutt that he is, he was ringed by posse of security men; and that too in pacified and combed neighborhood.

What is pacification?:

Pacification and combing are routine policies and procedures applied to poor slum-dwellers in cities globally. The basic premise is slums crawl with criminals, drug dealers, prostitutes, pimps, racketeers, black-marketers, assorted gangsters and gunmen on hire. The police have no control on such territories. Often, policemen take their sides. The underprivileged and destitute population does not have marketable skills to get jobs in a knowledge society. They eke out their livelihood from criminal and illegal activities in this unfair, unjust and inequitable world. They steal basic amenities like water, electricity, and subsidized cooking gas. They lurk on street corners and beaches hawking drugs, sex, maim and murder.

For the rich, powerful and beautiful populations living in palatial homes and luxurious high rises, they are eyesores; they deserve extermination and banishment. They must be returned to where they came from or at least must be hidden from their eyesight. But, they refuse to go away; each day a new favela is emerging. They acquire political power by supplying its musclemen and illegal guns both to the politicians and businessmen. They can get votes and customers for them. In the process, favelados legitimize their rights to the land and stolen amenities of life as long as the cocktail of gunmen, slumlords and politicians rule and the legitimate city government is emasculated.

Sounds familiar? Stung by international criticism about threats to the safety of soccer teams and fans for FIFA 2014 world cup as well as athletes and visitors for Olympics 2016, city government instituted an initiative to control street crime. Police Pacifying Units (UPP) were formed and using police and legal power first, the drug dealers and private militias were defeated; the favelas were brought under city control. Social programs including Community participation in peacekeeping and policing have shown results; 18 major favelas have been liberated by early 2012.

The program suffered a major setback in July 2012; regrouped and armed gangsters attacked UPP stations and killed a police officer. Police abuse and corruption were seen as hurdles in the war against private militias. The program had to deal with a new dimension: corruption of public servants and citizens.

The social inequalities are only widening:

Late in the night, after a sumptuous dinner in an expensive glitzy restaurant and bar, I settled down for a few Caipirinha shots at a Copacabana kiosk and marveled at the energy and sheer determination of people of my host city. It was near midnight and yet men and women played beach volleyball. Children ran around building sand castles even as waves washed them away. A white zombie woman, an obvious drug addict, lay on her back fully naked and covered only with sand. An amateur local band of guitarists and violinists strung away metal. Another group of boys and girls crooned with their shrill voices to the accompaniment of conches and drums. The young divorced woman street vendor of A-Z was busy negotiating even as her baby cried in the cradle in the makeshift pavement kiosk. Life has not improved for her, she had earlier told me. Life had not improved for my bodyguards either, who watched from their positions twenty yards away, each passerby in my vicinity as a potential robber.

I had seen this city and country adapt from the days of hyperinflation of eighties and early nineties, the recessionary years of late nineties and the confident years of this century. I had seen nearly every one of them black-marketers getting rid of their depreciating and worthless cruzado and cruzeiro for dollars to keep under their pillows. Today, they were proud of their stable currency Real. I had met rich professionals, directors, CEOs, COOs, metallurgists and engineers, for whom life had only gotten better over the years. In those days they wanted to emigrate for jobs. Today, they want to fly out only as tourists. The infamous social inequalities, the gap between the rich and poor, are widening. That is the real face of Rio, which it tries to mask each day. Unlike the annual Carnival masks of merriment, this mask is a problem the country and city should address now before it is too late.

The International Events are a starting point:

A few months before my last trip, Rio hosted the Pan American Games in July 2007. I had watched both opening and closing ceremonies on HDTV from Qatar and wondered at the exuberant energy. Brazil had arrived both as a sports power and organizer of international events. Fittingly, it won over its rivals to host World Youth Day in 2013, FIFA World Cup 2014, and Summer Olympics 2016. The Pope is expected to make the trip to join the World Youth Day celebrations. Even as Brazil and Rio has leapfrogged into a secure, stable, growing and rich economy at the head of BRIC nations, its most visible scar of social inequalities must be addressed. The poor cannot be wished away. The favelas cannot be demolished out of sight to make way for glitzy malls, hotels, bars and stadia. Peace must come to it streets through poverty alleviation. The will is there, opportunity is there, and actions must come.